I ran across the following discussion while reading the notes from the debate in the Massachusetts Ratifying Convention to discuss the adoption of the Federal Constitution, which took place in Boston from January 9, 1788 to February 5, 1788. This discussion was about whether the new rules about taxation were fair and focused on the “three fifth’s” rule which said that slaves counted as three-fifth’s a person for the purposes of State taxes and representation in the House of Representatives. Many of us have heard of the three-fifth’s rule, but it is startling to see how the rule was discussed in the north among those who otherwise were against slavery.

Here is the section of the Constitution to which the discussion refers.

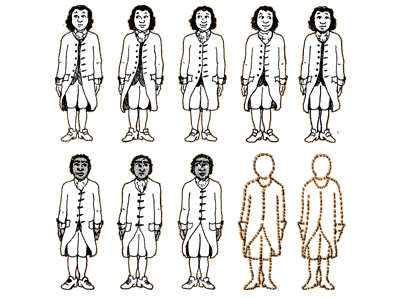

Article 1, Section 2: Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

The discussion in question takes place on Thursday Jan 17, 1788 <1>

Mr. [William] WIDGERY asked, if a boy of six years of age was to be considered as a free person.

Comment: Widgery was asking whether it was fair that Massachusetts would be taxed for a six year old and by implication suggesting that it was not fair. It was a good question really. Is a children a free person for the purposes of taxes? This was one of a number of complaints that Widgery had about the proposed constitution and Widgery was one of eight delegates who voted against the Constitution at the end of the Convention.

Mr. [Rufus] KING, in answer, said, all persons born free were to be considered as freemen; and, to make the idea of taxation by numbers more intelligible, said that five negro children of South Carolina are to pay as much tax as the three governors of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

Comment: Rufus King, was a lawyer who had been at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia and had worked closely with Alexander Hamilton to prepare the final draft, is arguing that this rule is good for Massachusetts. He is responding here to Widgery’s comment implying that it is not fair that minors count for purposes of taxation.

In response King is arguing that the north gets the advantage since the slave states would have to pay the same tax on five negro children as the Northern states pay on three productive adults – even governors. The three fifths rule, King is arguing, can be a northern advantage. It is worth noting that King had a long history of opposition to the expansion of slavery and the slave trade, a stand that was a product of moral conviction which coincided with the political realities of New England federalism.

Mr. GORHAM thought the proposed section much in favor of Massachusetts; and if it operated against any state, it was Pennsylvania, because they have more white persons bound than any other…

Comment: Nathaniel Gorham, was a delegate from Massachusetts to the Continental Congress, and for six months served as the presiding officer of that body. He also attended the Constitutional Convention and was one of the signers of the United States Constitution on September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Here Gorham is arguing that the section in question favored Massachussetts and if it hurt any state it hurt Pennsylvania which had more white people who were bound servants and who would count for purposes of taxes.

Mr. [Judge Francis] Dana….In reply to the remark of some gentlemen, that the Southern States were favored in this mode of apportionment, by having five of their negroes set against three persons in the Eastern, the honorable judge observed, that the negroes of the Southern States work no longer than when the eye of the driver is on them. Can, asked he, that land flourish like this, which is cultivated by the hands of freemen? and are not three of these independent freemen of more real advantage to a state than five of those poor slaves? As a friend to equal taxation, he rejoiced that an opportunity was presented, in this Constitution, to change this unjust mode of apportionment. Indeed, concluded he, from a survey of every part of the Constitution, I think it the best that the wisdom of men could suggest.

Comment: Judge Francis Dana is arguing against the position of Widgery who implied that the three fifth’s rule was to the advantage of the South. The advantage by implication was that slaves created revenue for the state but were taxed at a lower rate than whites. Invoking the stereotype of slaves as lazy if not supervised, he suggests that three free men are of equal value from a productivity standpoint (i.e., in creating revenue for the state) and therefore it makes sense that slaves would be counted less towards state taxes since their productivity was lower. He also notes that the Constitution leaves room for change in the future for what he calls “unjust apportionment.”

Francis Dana was an American lawyer, jurist, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served as a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1777–1778 and 1784. He signed the Articles of Confederation. An earnest advocate of the adoption of the Federal constitution, he was a member of the state convention which ratified it in 1788, and was one of the most influential advisers of the leaders of the Federalist Party.

Mr. NASSON remarked on the statement of the Hon. Mr. King, by saying that the honorable gentleman should have gone further, and shown us the other side of the question. It is a good rule that works both ways; and the gentleman should also have told us, that three of our infants in the cradle are to be rated as five of the working negroes of Virginia. Mr. N. [Nasson] adverted to a statement of Mr. King, who had said that five negro children of South Carolina were equally ratable as three governors of New England, and wished, he said, the honorable gentleman had considered this question upon the other side, as it would then appear that this state will pay as great a tax for three children in the cradle, as any of the Southern States will for five hearty, working negro men. He hoped, he said, while we were making a new government, we should make it better than the old one; for, if we had made a bad bargain before, as had been hinted, it was a reason why we should make a better one now….

Comment: Nasson and anti-federalist challenges Rufus King’s argument noting that the three fifth rule means that free white northern babies are counted equally to five working slaves. In other words, Massachusetts would be taxed for 3 nonroductive babies at the same rate the Southern States are taxed for five productive, revenue earning slaves. He continues by arguing that he had hoped the new government that the Constitution was to create would be better than the last (under the Articles of Confederation) and implies that this is one of the ways in which it would not be better for the north.

… discussion continues…

Mr. DAWES said, he was very sorry to hear so many objections raised against the paragraph under consideration. He thought them wholly unfounded; that the black inhabitants of the Southern States must be considered either as slaves, and as so much property, or in the character of so many freemen; if the former [I wonder if “if the latter” is meant], why should they not be wholly represented? Our own state laws and constitution would lead us to consider these blacks as freemen, and so indeed would our own ideas of natural justice. If, then, they are freemen, they might form an equal basis for representation as though they were all white inhabitants. In either view, therefore, he could not see that the Northern States would suffer, but directly to the contrary.

He thought, however, that gentlemen would do well to connect the passage in dispute with another article in the Constitution, that permits Congress, in the year 1808, wholly to prohibit the importation of slaves, and in the mean time to impose a duty of ten dollars a head on such blacks as should be imported before that period. Besides, by the new Constitution, every particular state is left to its own option totally to prohibit the introduction of slaves into its own territories. What could the Convention do more? The members of the Southern States, like ourselves, have their prejudices. It would not do to abolish slavery, by an act of Congress, in a moment, and so destroy what our southern brethren consider as property. But we may say, that, although slavery is not smitten by an apoplexy yet it has received a mortal wound, and will die of a consumption.

Comment: Mr T. Dawes (about whom I was unable to find any information) reminds the convention that the real issue is not the apportionment of taxes aligned to productivity but is the question of natural rights. Echoing a very similar statement made the Federal Constitutional Convention itself, Dawes comments on the absurdity of the three fifths rule, saying slaves should either be property and therefore treated like property, or freemen and therefore taxed at a whole person’s rate. He notes that Massachusetts law and ideas of natural justice would treat blacks as free persons. In either case he didn’t see that Northern States would suffer, but in fact thought it was to their advantage. He also notes that the Constitution has a provision that would allow Congress to prohibit slavery in 1808. He concludes with the pragmatic argument of those favoring compromise who argued that the Convention couldn’t have done more than it did to end slavery, since the Confederation didn’t have power to do so, and that it would not be fair to Southern states to abolish slavery swiftly. Still, he argues, that the institution has been dealt a blow by the new Constitution.

*****

1. This debate can be found in Jonathan Elliot, The Debates in the Several State Conventions of the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, vol. 2 [1827], 30-31.