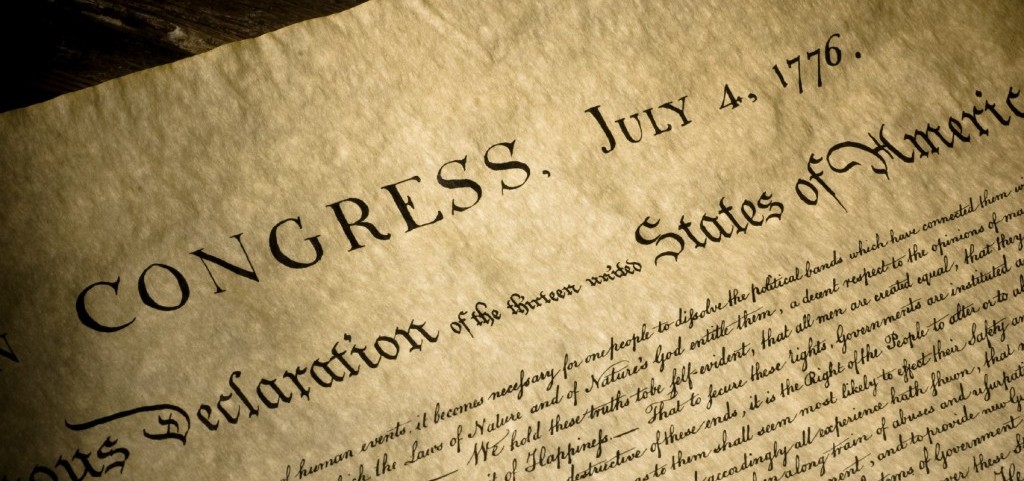

On the eve of July 4th, it is worth pausing and considering the theory of rights that is expressed in the document so often credited with the foundation of our American and individual rights: the Declaration of Independence.

It is not widely known that the author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, held a theory of American rights that differed widely from his colleagues in the colonies and in the Continental Congress. Jefferson actually tried to smuggle his theory of American rights into the Declaration when he wrote it but his view was edited out by the Committee of Five and by Congress as a whole, leading Jefferson to feel upset about the edits which he called “mutilations.” As a result, the Declaration of Independence actually papers over and even hides some important areas of disagreement over American rights among those favoring Independence. In particular, it does not address a key question in the debate over the rights of the colonies: what gave settlers their rights in general and to the lands they were living on.

The story begins two year earlier in 1774 when a thirty-one year old Jefferson wrote his first major political essay: A Summary View of the Rights of British America. It was an essay that helped Jefferson gain his reputation and get assigned to write the Declaration two years later. He wrote his first essay in preparation for the First Continental Congress, which was assembling to discuss the foundation of the colonies’ rights. Jefferson himself was unable to attend because he had dysentery. But he sent his essay along to his colleagues who assembled for the first Continental Congress.

In the essay, Jefferson articulated a theory of American rights at odds with that of most of his colleagues, though similar to that of his cousin Richard Bland, who was an elder statesman in the Virginia House of Burgesses. In the essay, Jefferson articulates the view that settlers to America came as free individuals who had quit their former states and set up new political societies on the American lands, which they had conquered or found vacant. Thus they were living, not in British colonies, but in independent legitimate political states. This view differed from the majority view of his colleagues, such as James Wilson and John Adams, among others, who held the view that the settlers came to the Americas under British auspices and settled as British subjects in British colonies with all the rights and liberties granted by the British common law.

This disagreement may not seem very significant today. But it was important enough that members of First Continental Congress actually debated the point in developing what became the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, and unofficially the first American Bill of Rights.

The details of the debate are evident from the notes taken by John Adams, who was representing Massachusetts, and who played a key role in the final wording of the document. Adams records how members of congress debated the source of their rights: Debate centered on whether those rights derived from nature, from their status as British citizens, or as individuals who had quit their societies of origin and founded new states under their own government. It was the latter position that Jefferson had articulated in his essay. After substantial debate, Congress rejected Jefferson’s view that the settlers had been individuals who founded their own societies. Instead they agreed to appeal to natural rights and to the rights of British citizens. Thus, resolution number 2 reads:

Resolved, N.C.D. 2. That our ancestors, who first settled these colonies, were at the time of their emigration from the mother country, entitled to all the rights, liberties, immunities of free and natural-born subjects, within the realm of England.

On the official view published by the First Continental Congress, the colonists had rights in part because they were British citizens. They brought their British rights with them.

Perhaps Jefferson’s view that the settlers had quit their countries of origin and set up new societies was too radical for the first Continental Congress. That would make some sense, except for the fact that Congress rejected Jefferson’s position two more times including in his first draft of the Declaration.

In Jefferson’s first draft of the Declaration, he wrote that:

When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for a people to advance from that subordination in which they have hitherto remained, & to assume among the power of the earth the equal & independent station to which the laws of nature & of nature’s god entitle them….

In the editorial revision by the Committee of Five, which included Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, the words have changed as follows:

When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for a [one] people to advance from that subordination in which they have hitherto remained, & to assume among the power of the earth the [separate and equal] equal & independent station to which the laws of nature & of nature’s god entitle them….

In the edits of Congress, it becomes clear that the American states were originally “one” people with the British and the assertion of independence is to give them “separate and equal” power. In Jefferson’s original language, by contrast, the American political entities were “a” separate people from the start, but one that had been subordinated. This is one example of several where the language of Jefferson’s first draft is edited by Congress in order to position the colonies as part of British Empire whose rights have been violated.

Given that the Declaration was an assertion of independence, there was no reason to be more circumspect as there has been in 1774 when the First Continental Congress first put together its first declaration of rights. Thus the theoretical disagreements hidden in the Declaration point to substantive differences among the founders over the justification of American rights.

This is just one of the fundamental disagreements about rights that the Declaration papers over and hides. Another is the justification by which the American people can claim to have rights to the land. In general the founders didn’t talk about that issue much at all. When they did, they disagreed whether the lands were unoccupied, or had been taken in conquest, and whether that conquest had been justified. But that is another story for another time.

On the eve of July 4th, it is useful to remember that there was never one theory of American rights and that the intent or meaning of the founding documents, even the one that tells us about the foundation of our rights, is never completely unequivocal. History can often open our eyes, but it can’t ultimately resolve our own current debates about what rights we have or do not have.

_________________

*For more about the ambiguities in Jefferson’s Declaration, see my Liberty in America’s Founding moment: Doubts about Natural Rights in Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence.

*Notes from the First Continental Congress.